Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation

During pregnancy the mother and the fetus form a non-separable functional unit. Maternal well-being is an absolute prerequisite for the optimal functioning and development of both parts of this unit. Consequently, it is important to treat the mother whenever needed while protecting the unborn to the greatest possible extent. Drugs can have harmful effects on the fetus at any time during pregnancy. It is important to remember this when prescribing for a woman of childbearing age. The past use of stilboesterol in pregnant women with threatened abortion has resulted in development of adenocarcinoma of vagina in female children in their teens and early 20s. However, irrational fear of using drugs during pregnancy can also result in harm. This includes untreated illness, impaired maternal compliance, suboptimal treatment and treatment failures.

Such approaches may impose risk to maternal well-being, and may also affect the unborn child. It is important to know the ‘background risk’ in the context of the prevalence of drug-induced adverse pregnancy outcomes. Major congenital malformations occur in 2–4% of all live births. Up to 15% of all diagnosed pregnancies will result in fetal loss. The cause of these adverse pregnancy outcomes is understood in only a minority of the incidents.

Prescribing in Pregnancy:

In the placenta maternal blood is separated from fetal blood by a cellular membrane. Drugs can cross the placenta by active transport or by passive diffusion down the concentration gradient, and it is the latter which is usually involved in drug transfer. Placental function is also modified by changes in blood flow, and drug which reduce placental blood flow can reduce birth weight. This may be the mechanism which causes the small reduction in birth weight following treatment of the mother with b-blockers in pregnancy. Early in embryonic development, exogenous substances accumulate in the neuroectoderm. The blood-brain barrier to diffusion is not developed until the second half of pregnancy, and the susceptibility of the central nervous system (CNS) to developmental toxins may be partly related to this. The human placenta possesses multiple enzymes that are primarily involved with endogenous steroid metabolism but may also contribute to drug metabolism and clearance.

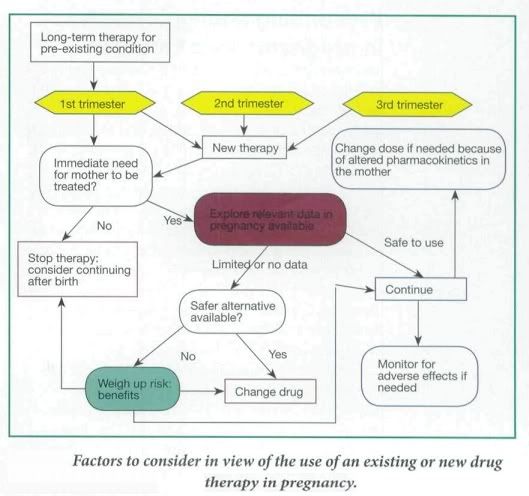

Factors to Consider

In general, most women of child-bearing age are young, fit and healthy. However in some cases the mother is on an established therapy for a pre-existing condition, such as depression or epilepsy, or she may develop a pregnancy-induced medical condition, such as hypertension or gestational diabetes. Therefore the aim of drug therapy is to limit any damage to the growing fetus while still being able to treat the mother appropriately. Ideally a detailed risk:benefit assessment of drug therapy in pregnancy should be conducted.

- The trimester in which the drug is being taken,

- What dose of drug is being taken,

- If the drug is at the lowest effective dose possible,

- How much is being passed through the placenta to the fetus and, consequently,

- If the drug is known to be teratogenic

- Total body water and plasma volume increase during pregnancy. In addition, the concentration of plasma albumin falls, reducing protein binding of drug and consequently increasing drug plasma levels. Hence doses of highly protein-bound drugs might need to be reduced (Phenytoin, Warfarin etc.)

- Pharmacokinetics of drug metabolism may differ in a woman during pregnancy and consequently this would need to be taken in to account during drug dosing. ( maternal underactive thyroid gland that has previously been controlled by taking levothyroxine at a particular dose may well need to be increased)

- Drugs taken during pregnancy can act directly on the fetus causing spontaneous abortion, fetal malformations, or have no effect.

- Drugs can also cause oxidative stress which can result in underdevelopment and malnutrition.

- Usually very early in pregnancy, before the 20th day, there is an all-or-nothing effect whereby the fetus will abort spontaneously if the drug has caused harm, or there will be no detrimental effects to the developing fetus (Mother is usually unaware).

- Between days 21 and 56 {approximately), following fertilization, the fetus is very susceptible to birth defects and this is when the mother has usually just realized that she is pregnant. This is the stage of organogenesis and drugs used at this stage may interfere in their development and cause a fetal malformation, or the defect may be more subtle and may not affect function to a debilitating extent or may even lead to a miscarriage.

The stage of gestation influences the effects of drugs on the fetus. It is convenient to divide pregnancy into four stages: fertilization and implatation (<>organogenesis/embryonic stage (17-57 days), the fetogenic stage and delivery.

The principal mode of contraceptive action of progestrogens is to prevent implantation, which normally occurs 2-3 weeks after fertilization. IUCD have similar effect. Damage to the embryo before implantation results in failure of implantation and is therefore unlikely to cause fetal abnormalities.

Effects on Organogenesis/embryonic stage

The intra-uterine period between 2 weeks – 3 months is when the most serious abnormalities of fetal development can be caused by drugs. It’s during this period that the major organs are being formed. In animal studies, even one dose of a drug administered at the critical time has been shown to have a major effect.

At this stage the fetus is differentiating to form major organs and this is the critical period for teratogenesis. Teratogens cause deviations or abnormalities in the development of the embryo that are compatible with prenatal life and observable postnatally. Drugs that interfere with this process can cause gross structural defects, for example thalidomide phocomelia.

Some drugs are confirmed teratogens, but for many the evidence is inconclusive. Thalidomide was unusual in the way in which a very small dose of the drug given on only one or two occasions between the fourth and seventh weeks of pregnancy produced serious malformations. Despite its wide use it was nearly 4 years before these adverse effects were recognized.

Some drugs that are definitely teratogenic in humans.

Thalidomide Cytotoxic agents Alcohol Warfarin Retinoids Most anticonvulsants | Androgens Progestogens Diethylstilbestrol Radioisotopes Some live vaccines Lithium |

Toxicity to the formed fetus

During T2 & T3 of pregnancy, adverse effects on fetus of drugs administered to the mother are generally an exaggeration of the effects seen in the adult. Exception to this rule are the damage to tissues which are still developing e.g. teeth & bones by Tetracycline, and the impairment of brain development by Coumarin anticoagulant.

Particular care must be taken with drugs given shortly before delivery. Analgesics, e.g. Meperidine (Pethidine), and tranquillizers e.g. (Benzodiazepines) may severely impair neonatal respiration. In addition, the newborn lacks many enzyme necessary for the efficient metabolism of drugs.

Adverse effects of drugs on fetal growth and development.

- Drugs used to tread maternal hyperthyroidism can cause fetal and neonatal hypothyroidism - Tetracycline antibiotics inhibit growth of fetal bones and stain teeth - Aminoglycosides cause fetal VIIIth nerve damage - Opioids and cocaine taken regularly during pregnancy can lead to fetal drug dependency |

Delivery

Some drugs given late in pregnancy or during delivery may cause particular problems. Pethidine, regularly administered as an analgesic can cause fetal apnea (which is reversed with naloxone). Anesthetic agents given during Cesarian section may transiently depress neurological, respiratory and muscular functions. Warfarin given in late pregnancy causes a hemostasis defect in the baby and predisposes to cerebral hemorrhage during delivery.

Prescribing in Lactation:

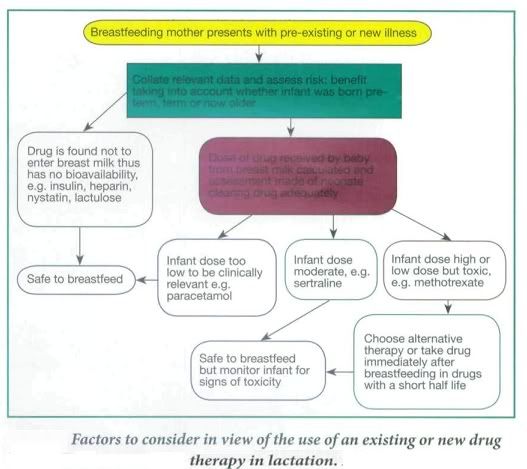

During breast feeding unintentional passage of any drug to the baby through the breast milk and the effects on the newborn must be considered. In pregnancy the mother's circulation eliminates the drug for the fetus, but once born the neonate has to clear any drug itself when the organs for drug elimination (liver and kidney) are more fragile and not functioning optimally.

It is preferable that the mother stays on stabilized medication during pregnancy and continues while breastfeeding to avoid adverse or other side-effects from changing to another drug, such as with antidepressants. However, in some cases otherwise acceptable drugs used in pregnancy are contraindicated after delivery or in breastfeeding, and prescribing an alternative, more appropriate drug would be considered at this stage. For example, methyldopa is the drug of choice for high blood pressure in pregnancy and although it is also safe in lactation, there is an increased risk of postnatal depression in women taking methyldopa; therefore it would be changed to an alternative drug postnatally.

Other factors to consider in prescribing in lactating mothers is the percentage of the drug passed into breast milk, its half-life, and whether the baby was born at term and is healthy and able to tolerate this drug, which would depend on its gestational age. Drugs taken by the mother may not be absorbed - Fybogel, Lactulose, some antibiotics such as oral vancomycin, or the antifungal, nystatin, Insulin and heparin are too large to pass into breast milk and these are usually safe. Some drugs pass in to breast milk in small amounts. In some cases this would be below therapeutic levels in the baby so would not appear to cause any adverse effects. However, a neonates organs are not fully functioning in the first few weeks of life meaning a drug could potentially accumulate over days in the neonates bloodstream, which may cause adverse side- effects. In other cases even small amounts of a drug can be harmful to the neonate, e.g. methotrexate and should therefore be avoided altogether, or the mother should consider not breastfeeding.

Specific scenarios:

- Analgesia in pregnancy and lactation:

- The drug of choice for pain relief in pregnancy is paracetamol.

- Weak opioids like codeine may be used if pain is not manageable.

- Pethidine is used as analgesia in labour as it is short- acting and its effects can be controlled.

- NSAIDs are altogether avoided because of risk to premature closure of ductus arteriosus, high risk of miscarriage due to inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis - however low dose aspirin might be used in women with PIH, umbilical placental insufficiency and clotting disorders such as lupus coagulant, Factor V Leiden and protein C deficiency, or pre-eclampsia.

- Drug of choice for pain relief during lactation is paracetamol. Tn the case of more severe pain, NSAIDs such as ibuprofen and diclofenac, are preferred. Although aspirin passes into breast milk in only small amounts, it should be avoided to prevent the risk of Reye's syndrome in children.

- Weak opiates, such as codeine and dihydrocodeine, may be used in lactation but can cause colic and constipation in the infant.

- Antihypertensives in pregnancy and lactation:

- Angiotensin II receptor antagonists, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and the beta blocker, atenolo!, are contraindicated in pregnancy because of their adverse effects on the fetus and fetal growth.

- Drugs of choice to lower high blood pressure in pregnancy are methyldopa, labetalol or nifedipine, all of which have been used safely previously.

- Some beta blockers that have low protein binding, e.g. atenolol and acebutolol, increase bioavailability of the drug in breast milk and should be avoided because of the effects of neonatal bradycardia, otherwise all anti-hypertensives are safe during lactation.

- Antidepressants in pregnancy and lactation:

- The SSRIs (citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine and sertraline) are now most commonly prescribed to new patients as they are better tolerated than other classes of antidepressants.

- Fluoxetine has been the most extensively studied of the SSRIs in pregnancy and offers no increased risk of miscarriage, malformation or neurodevelopment to the fetus and long term.

- The SSRIs of choice for lactating women are those with the shortest half-life, i.e. tluvoxamine, paroxetine or sertraline with half lives between 17 and 26 hours. However, infants should be monitored for symptoms (owing to drug accumulation) such as excessive crying, poor sleep, irritability and colic.

- Anticonvulsants in pregnancy and lactation:

- Epilepsy in pregnancy can lead to fetal and maternal morbidity/mortality through convulsions whilst all the anticonvulsants used have been associated with teratogenic effects, for example phenytoin is associated with cleft palate and congenital heart disease.

- However, there is not doubt the benefits of good seizure control outweigh the drug-induced teratogenic risk.

- Thorough explanation to the mother, ideally before a planned pregnancy, is essential and it must be emphasized that the majority of epileptic mothers haver normal babies (>90%). (The usual risk of fetal malformation is about 2%. In epileptic mothers it is up to 10%).

- In view of the association of spina bifida with sodium valproate and carbamazepine therapy it is often recommended that the standard dose of folic acid be increased to 4-5 mg daily. Both these anticonvulsants cause hypospadias.

- As in non-pregnant epilepsy single drug therapy is preferable.

- Plasma concentration monitoring is particularly relevant for phenytoin because the decrease in plasma protein binding and the increase in hepatic metabolism may cause considerable changes in the plasma concentration of free (active.

- Antiemetics in pregnancy and lactation:

Nausea and vomiting are common in early pregnancy but are usually self-limiting and ideally should be managed with reassurance and non-drug strategies such as small frequent meals, avoiding large volumes of fluid and raising the head of the bed.

If symptoms are prolonged or severe, drug treatment may be effective.

Meclozine and cyclizine are commonly used although both have been weakly associated with an increased risk of congenital malformations.

Metoclopramide is considered safe and efficacious in labor and before anesthesia in late pregnancy but its routine use in early pregnancy cannot be recommended because of lack of controlled data, and a significant incidence of dystonic reactions in young women.

Drugs for Acid-peptic and constipation during pregnancy and lactation:

The high incidence of dyspepsia due to gastro-esophageal reflux in the second and third trimesters is probably related to the reduction in lower esophageal sphincter pressure.

Non-drug treatment - reassurance, small frequent meals and advice on posture - should be pursued in the first instance particularly in the first trimester. Fortunately most cases occur later in pregnancy when non-absorbable antacids such as alginates should be used.

In late pregnancy metoclopramide is particularly effective as it increases lower esophageal sphincter pressure.

There are inadequate safety data on the use of H2-receptor blockers and omeprazole in pregnancy.

- Sucralfate has been recommended for use in pregnancy in the USA and is rational as it is not systemically absorbed.

- Misoprostol, a prostaglandin which stimulates the uterus, is contraindicated because it causes abortion.

Constipation should be managed with dietary advice. Stimulant laxatives may be uterotonic and should be avoided if possible.

- Anticoagulants in pregnancy and lactation:

Warfarin has been associated with nasal hypoplasia and chondrodysplasia when given in the first trimester and CNS abnormalities after administration in later pregnancy, as well as a high incidence of hemorrhagic complications towards the end of pregnancy. Neonatal hemorrhage is difficult to prevent because of the immature enzymes in fetal liver and low stores of vitamin K.

Heparin, which does not cross the placenta, is the anticoagulant of choice in pregnancy although chronic use can cause maternal osteoporosis.

Women on long-term oral anticoagulants should be warned that these drugs are likely to affect the fetus in early pregnancy.

Subcutaneous heparin (usually self-administered) must be substituted for warfarin as soon as possible, well before the critical period of 6-9 weeks´ gestation. Subcutaneous heparin can be continued throughout pregnancy but due to the risk of maternal osteoporosis and thrombocytopenia warfarin may be considered as an alternative during the second trimester changing back to heparin at 36 weeks.

Patients with prosthetic heart values present a special problem: in these patients in spite of the risk to the fetus warfarin is often given up to 36 weeks.

The prothrombin time/international normalized ratio (INR) (warfarin) or APTT (activated partial thromboplastin time) (heparin) should be monitored closely.

Hormones in pregnancy and lactation:

- Progestogens, particularly synthetic ones, can masculinize the female fetus. There is no evidence that this occurs with the small amount of progestogen (or estrogen) in the oral contraceptive: the risk applies to large doses.

- Corticosteroids do not appear to give rise to any serious problems when given via inhalation or in short courses. Transient suppression of the fetal hypotlalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis has been reported. Rarely cleft palate and congenital cataract have been linked with steroids in pregnancy but the benefit of treatment usually outweighs any such risk.

Conclusion:

- A detailed risk:benefit assessment of drug therapy in pregnancy should be conducted.

- There are altered pharmacokinetics in the pregnant woman affecting drug metabolism and elimination.

- It is important to consider the trimester of pregnancy when prescribing.

- Known teratogenic drugs must be avoided in pregnancy.

- Some acceptable drugs used in pregnancy may be contraindicated after delivery or in breastfeeding and vice versa; the two should be considered independently.

- Drug prescribing in the breastfeeding mother depends on the percentage of drug passed in to breast milk, the drug half-life, and whether the baby was born at term and is healthy.

2 comments

Leave a reply

Nice work Vishaal! This will help me a lot! Where did you refer this from? Keep up the good work.

@ Gurudutt Nayak-

Referred a few journal articles and books.